Baptizing America: a critique

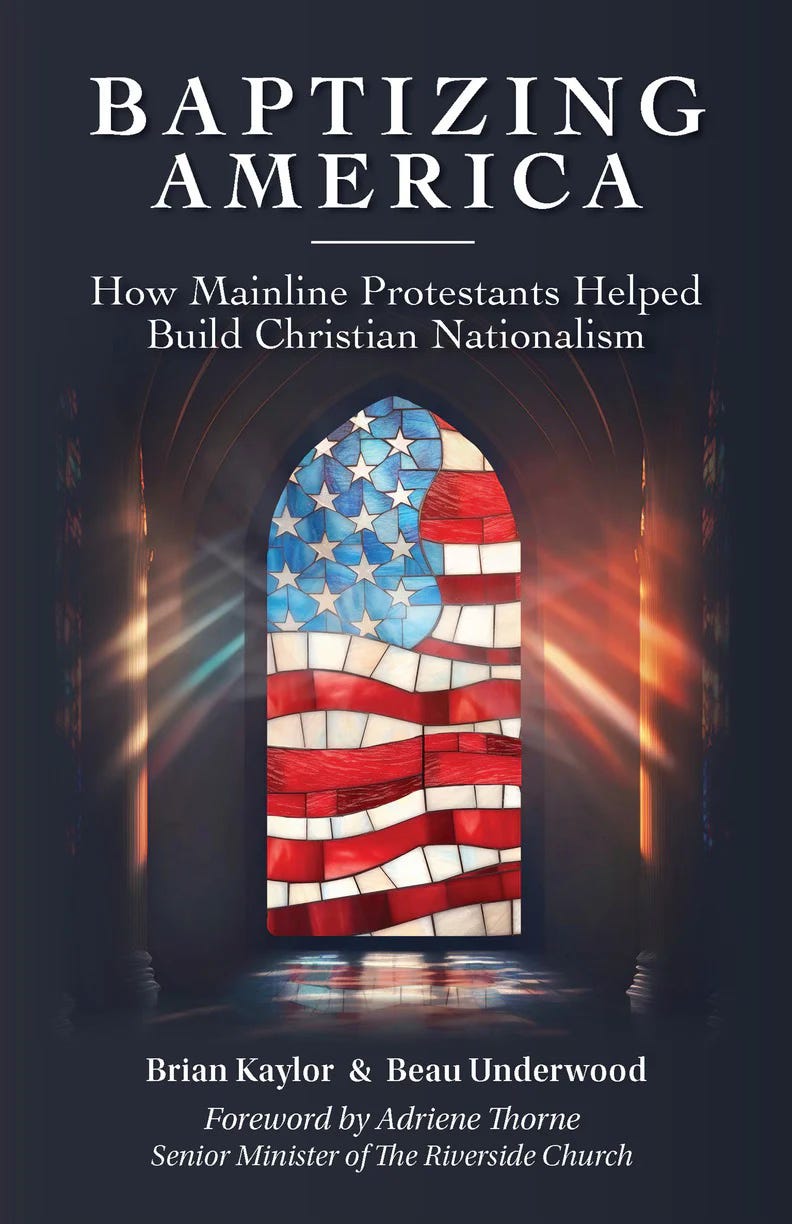

Baptizing America: How Mainline Protestants Helped Build Christian Nationalism, by Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood.

Am I in the right place?

As a college admissions representative for my alma mater, I was still learning my way around. My role recruiting students took me to public and private high schools in a three-state region. When I entered the high school in this little East Iowa town I saw a statue of Mary displayed in the entrance.

I paused.

My calendar confirmed it was supposed to be a public school, but did I miss something? About that time, the bell rang, and the hallway flooded with students, some wearing standard parochial school uniforms - girls in plaid skirts and boys in khakis and polos. I asked directions to the counselor’s office. When I arrived and after exchanged pleasantries, I asked the counselor the question:

“Is this a public or a private high school?”

Turns out it was public.

“So what’s the deal with the statue of Mary?”

The answer: 97.5 percent of the town’s population was Catholic. The other 1.5 percent were Lutheran and they were fine with the statue, according to the school counselor.

After a year, I left for another job so I never returned to that school and have no idea if the statue or even the school is still there. But that experience stuck with me. I grew up valuing the concept of Separation of Church and State and the freedom of religion protected by the U.S. Constitution, but was aware of inconsistencies all around me in public spaces and church spaces alike. So when Brian Kaylor and Beau Underwood published their book Baptizing America: How Mainline Protestants Helped Build Christian Nationalism, I anxiously pre-ordered my copy. It came this week and I read it.

There were a lot of ‘aha’ moments for me, like when they explained how American flags have become a permanent fixture at the front of American church auditoriums. The first section offers the context for their thesis with lots of footnotes. They continue the footnotes throughout the book, demonstrating a thorough understanding of the material and many sources for reference to those wishing to go deeper. The final three sections will appeal to the curious as well as the scholar, and the whole book, 199 pages in all, is very accessible.

Baptizing America takes a revealing look at how the American church has flirted with Christian Nationalism from its inception. Kaylor and Underwood take a closer look at the timeframe from the end of WWII through the 1970s when mainline churches enjoyed a position of societal prominence and used that influence to invite symbols of government into their church houses and install church blessings into government voices and spaces.

Flags began appearing in church houses in the 19th Century. During and after the Civil War they were expressions of loyalty to the Union. During the wars of the 20th Century, they became an almost universal presence as Christians sought God’s protection and victory.

In 1953, a prayer room or chapel was built in the Capitol just for legislators - it's not open to the public.

The National Day of Prayer was established in 1953 as a private event but with obvious and intentional trappings of official government sanction that has grown and today unapologetically promotes Christian Nationalism.

In 1954, “under God” was added to the Pledge of Allegiance after more than 60 years of use without those words.

Coins were inscribed “In God We Trust” since the Civil War, but in 1954, the motto was promoted for use on stamps, government buildings and about any location it could be printed, etched or engraved. it’s no accident that many of these actions occurred or were accelerated during the Eisenhower administration.

By the Bi-Centennial in 1976, the Baptizing of America was almost complete as churches of all stripes, including and especially mainline churches encouraged the incorporation of national symbols and elements into worship services during the Bi-Centennial celebration.

The Doctrine of Civil Religion

“…(T)he U.S. founders did not try to create the U.S. as a ‘Christian’ nation and instead used religion in ways (Robert Bellah) referred to as ‘civil religion.’ Like generations of scholars between him and us, we find his historical analysis convincing. He clearly captured something important about how the founders talked about a ‘Creator,’ ‘Providence,’ and ‘Nature’s God.’ This concept of civil religion reflects ‘a genuine apprehension of universal and transcendent religious reality as seen in or, one could almost say, as revealed through the experience of the American people.’ Yet, such participation in the sacred through one’s citizenship does not involve ‘the worship of the American nation but an understanding of the American experience in the light of ultimate and universal reality.’

Robert N.Bella, “Civil Religion in America,” Daedalus 96, no. 1 (1967):18. (Baptizing America, pg. 39)

The language of the Christian religion, through what Robert Bella (see quote above) called ‘Civil Religion’ has helped our nation’s leaders articulate shared goals and initiatives, shared victories and mourning from the time of the founders until recently. A majority of Americans understood the shared experience, vocabulary and symbols of Christianity that even non-adherents of the faith often recognized as their own. Children learned to read from scriptures in frontier schools where the only book was the Bible. They learned the stories of the Bible through the 19th Century Sunday School movement that swept the country well into the 20th Century. They recognized the symbols in literature and the arts. It was only natural that politicians and other civic leaders chose the vocabulary of Christianity to connect with their constituents.

Civil religion, intended to unite, could also divide. From the American Civil War to the 1960s civil rights movement, advocates used the language of Civil Religion to promote their causes and move the nation. Kaylor and Underwood suggest Civil Religion has become an anachronism as demographics shift and Christianity’s cultural and societal impact decreases. Christian language and symbols have lost the power to move the whole nation and, instead have become increasingly divisive. Many Christians now embrace Christian Nationalism as a reactionary movement intent on returning America to an imagined earlier time, distorting our nation’s origin story, insisting Christians founded this country and Christianity and its followers should govern our nation; a stance that endangers democracy itself.

I was 15 years old in 1976. I’d grown up during this time when civil religion was deeply woven into the fabric of American life. People with my long memory were the frogs in the pot, cozy with the water lapping at our necks, all the while the temperature is rising dangerously higher and higher. No wonder so many of my generation and older didn’t see it and many still don’t. Calling it out as Christian Nationalism, as Kaylor and Underwood have done, is not an overreach. It’s a shouted warning of the danger in which we’ve placed ourselves.

Kaylor and Underwood critique the role that Evangelicals have played in giving Christian Nationalism a boost. They acknowledge the role of Evangelicalism in the rise of Christian Nationalism is well-documented. With Baptizing America, they make a case that Mainline churches helped pave the way for the heresy. Both Kaylor have indirect and direct connections to Mainline churches. Underwood is the pastor of a Disciples of Christ church in Indianapolis. As Kaylor and Underwood say: “Mainline leaders, denominations and churches wanting to address Christian Nationalism can start by looking in the mirror. They can acknowledge and remedy their own contributions to the spread of this ideology.”

“The myth of America as a Christian nation, with the church as its guardian, has been, and continues to be, damaging both to the church and to the advancement. of God’s kingdom. … This myth harms the church’s primary mission. For many in America and around the world, the American flag has smothered the glory of the cross, and the ugliness of our American version of Caesar has squelched the radiant love of Christ. Because the myth that America is a Christian nation has led many to associate America with Christ, many now hear the good news of Jesus only as American news, capitalistic news, imperialistic news, exploitive news, antigay news, or Republican news.”

Gregory A. Boyd, The Myth of a Christian Nation: How the Quest for Political Power is Destroying the Church (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2005), 13-14. (Baptizing America, pg. 195)

I’ve known Kaylor and Underwood for a number of years. I am a board member of Word & Way, an independent Christian media outlet, where Kaylor serves as President and Editor-in-Chief and Beau was a former editor and writer while serving as pastor of a local congregation. I’m proud of their achievement with this book and am grateful for the prophetic voices they bring in support of the principle of Separation of Church and State.

Brian Kaylor and Beau Underwood. Baptizing America: How Mainline Protestants Helped Build Christian Nationalism. Nashville: Chalice Press, 2024.

https://chalicepress.com/products/baptizing-america?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

Thanks for this brief review. It’s a priority on my reading list! I fear the frog in the pot of boiling water has little time to act!